Bernard Faÿ, one of six French visiting professors at the 1923 Columbia Summer Session (photo taken in 1924)

HE LIST OF FRENCH VISITORS AT COLUMBIA OVER THE PAST 100 YEARS—invited by the Maison Française, the Department of French, or the university—is long and distinguished. Behind every visit there is a story. Here are just a few of the more memorable ones.

COLUMBIA SUMMER SESSION, 1923

On February 25, 1923, The New York Times announced: “Columbia Attracts Scholars of World. A group of French men of letters will be the centre of a world gathering of scholars at Columbia University during the Summer session.” Six French scholars, “selected from among the very best,” sailed to New York. Joseph Bédier, Émile Bourgeois, Paul Hazard, Édouard Le Roy, Raoul Blanchard, and Bernard Faÿ gave individual seminars and together team-taught a grandiose course on “French Civilization,” with an opening lecture by French Ambassador J. J. Jusserand. The idea, not surprisingly, was Butler’s, and the entire undertaking was hailed as the outstanding feature of the summer session, which offered 1,000 courses to 13,000 students. “The French program is the most ambitious ever undertaken at a Columbia Summer Session, a further step in the general effort of the educational institutions of France and America to bring the two peoples into more intimate intellectual contact,” said the Times. Students became “thoroughly acquainted with all that is most brilliant and most significant in French culture without having to leave New York to find it.”

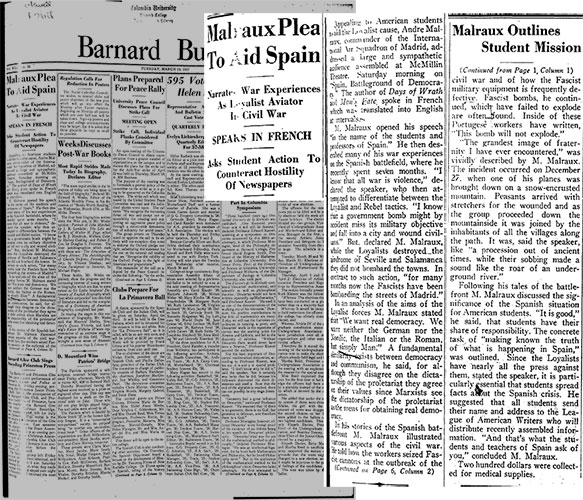

ANDRÉ MALRAUX, 1937

On March 20, 1937, André Malraux gave a lecture in French at Columbia’s McMillin (now Miller) Theatre during a speaking tour of the U.S. The 36-year-old left-wing author of Man’s Fate and Days of Wrath had just spent half a year fighting in the Spanish Civil War. In an amateur recording of his speech that survives today, we hear Malraux speak about revolution and history, but he talks mostly about the war. At one point he describes how a plane in his squadron was shot down in the snow-covered mountains of northern Spain. Peasants placed the wounded on stretchers, and brought them slowly down winding mule paths toward the valley. The peasants waiting down below did not visibly react to the first men, injured in the legs. “But when those wounded in the face began to arrive—flat bandages showing where the noses had been torn off, streams of dried blood on their leather jackets—the effect was completely different, and the women and children began to weep. It was the most gripping image of fraternité I think I have ever seen in my life,” Malraux said. “The great silence, the mountain covered from the summit to the base with Spanish people who had followed these men who had come from every country on earth to defend what they believed to be right.” This became a central scene in L’Espoir (Man’s Hope), the Spanish Civil War novel that Malraux was writing during his New York trip. Malraux ended his speech with an appeal to Columbia students and professors to help fight Franco by doing what they did best as intellectuals: learning the truth about Spain, reading the dispatches being sent by the Spanish Republicans to the Association of American Writers, and speaking out to everyone around them. “If 1,000 or 2,000 of you do this work in service of the truth,” he said, “this will help us more than all the money sent to care for our wounded.”

ALBERT CAMUS, VERCORS, THIMERAIS, 1946

“No American Francophile could remember any lecture in French that had ever drawn an audience of more than 300 in New York. Yet, on March 28, 1946, we were to be at least four times that many in Columbia’s McMillin Theatre. The three lecturers were named Vercors, Thimerais, Albert Camus.” This was how Professor Justin O’Brien remembered Camus’ visit to Columbia to debate “the crisis of man” during his first trip to the U.S., sent by the French government. The young editor of Combat was greatly admired in France for his Resistance work and for such writings as L’Étranger, published in English as The Stranger during his U.S. stay. O’Brien remembered, “When he told us that, as human beings of the twentieth century, we were all of us responsible for the war, and even for the horrors we had just been fighting (the concentration camps, extermination by gas), all of us in the huge hall were convinced, I think, of our common culpability. Then Camus—who was never one to castigate without embodying an affirmative suggestion in his sermon—told us how we could contribute, even in the humblest way, to reestablishing the honesty and dignity of men.” O’Brien learned that, during the talk, thieves had stolen the box office receipts, which were intended for French war orphans. He announced the theft to the audience, saying that the “crisis of mankind” was at their door. Someone stood up and suggested that everyone pay for their ticket again on the way out, and, “under the spell of Camus’ persuasive words,” this is indeed what happened. The second take was more than the amount stolen.

A few days later, Camus met informally with Columbia undergraduates at the Maison Française. Eugene Sheffer remembered that “Mr. Camus asked more questions than the students themselves. He was very curious about the young American student: how he thought, how he reacted to the contemporary scene.”

Camus’ U.S. visit raised concerns for J. Edgar Hoover, who conducted an FBI investigation of the author. The FBI file refers to his talk at Columbia but notes that, “According to informant, subject’s lectures merely intended to show France’s cultural attitude so as to foster a closer relationship between the culture of France and the U.S. and also to express his philosophy of the absurd man.” Camus’ FBI file concludes: “Investigation fails to develop any subversive or political activity on subject’s part.”