Columbia student at military training camp, summer 1916, before the U.S. entered the war

HE WAR THAT BROKE OUT IN EUROPE JUST ONE YEAR AFTER THE FOUNDING OF THE MAISON FRANÇAISE helped to forge a special relationship between Columbia and France, just as it bolstered French-U.S. relations and triggered a shift in American sentiments in favor of France and against its enemy, Germany. As a symbol of this change in fortunes, the Deutsches Haus as such was closed and renamed “Columbia House” in April 1917. (It reopened as the “Deutsches Haus” in 1929, but was closed again during World War II.) Meanwhile, the France-America Society rallied pro-French opinion out of its headquarters at the Maison Française.

Some biographies of Nicholas Murray Butler state that he remained strictly neutral before the U.S. entered the conflict in April 1917. And while he did continue to defend internationalist principles and called for a federalist “United States of Europe” and stronger international institutions to ensure a lasting peace, Butler’s actions during the war, his role as president of the France-America Society, and accounts in French news sources suggest that early on his sympathies lay with France and the Allies. Articles in French newspapers like Le Temps lauded Butler, “who, from the beginning of the war, took initiatives in favor of France and whose generous and efficient actions contributed to preparing American intervention” (April 20, 1917). Paul Henri d’Estournelles de Constant credited him for leading “our mutual campaign against the universal danger of German aggression” (The New York Times, June 8, 1919).

Two anecdotes illustrate Butler’s pro-French stance before 1917. On Bastille Day in 1915, he hosted a dinner at the president’s mansion. A French guest recalled the scene: “The guests started arriving. Here were a former Secretary of State, high officials of the G.O.P., celebrated writers, two very famous artists, eminent professors with their wives. In the vast entryway was a life-size portrait of General Joffre. During the whole dinner, we spoke only of the war. We exalted the heroism of the French Army and the excellence of its commanders. When dessert was served, Dr. Butler proclaimed ‘Hail France! Hail France! Vive la France!’ and saluted ‘our oldest and dearest friend, our most gallant and courageous ally: France.’”

And in a letter to the president of the Sorbonne dated March 31, 1916, Butler wrote, “You can hardly realize the anxiety with which we follow every development in the war, particularly on the Western Front. The magnificent defense of the French Armies at Verdun has filled us all with new admiration for what I consider, without any hesitation, the most remarkable people in history. What the Greeks were in ancient civilization the French are in the civilization of to-day and to-morrow.”

Before the U.S. entered the war, many Columbians participated in relief work or joined as volunteers. Forty-nine School of Nursing graduates volunteered for service in 1915. Some forty-five Columbia students drove ambulances in France with the American Field Service, founded during the war as a volunteer ambulance corps that attracted many Ivy League students. Even the 54-year-old Raymond Weeks, professor of Romance philology, went to France with the AFS for six months, earning the French Legion of Honor.

Despite U.S. neutrality, Columbia began gearing up for war by May 1916, when the university held a mass meeting to pledge support for “war preparedness.” As a result, 500 Columbia student and alumni volunteers traveled to Plattsburg, New York, for summer training that year. In February 1917 Columbia publicly severed relations with Germany, formed a committee on national defense, and adopted a plan to organize for national service, soon touted by the U.S. government as a model for all American colleges. Next it formed a Reserve Officers Training Corps. Columbia faculty members signed two petitions to President Wilson before April 1917, one condemning Germany’s treatment of the Belgians, and the other urging the president to join the conflict and help finance France’s war costs, not as a loan, but as “repayment” for French aid during the Revolutionary War.

Once the U.S. finally joined the conflict, Butler put Columbia on a war footing, and threatened “the separation of any person from Columbia” who “acts, speaks or writes treason.” The campus took on a militaristic atmosphere. Approximately 1,400 students were enrolled in the Columbia R.O.T.C. in 1917, and 300 eventually went into officer training. Columbia provided specialized military training and established a war hospital. The entire student body was enrolled in the Student Army Training Corps in October 1918 and placed under strict military routine—army uniforms, sleeping on cots, morning reveille and roll call at 6 a.m., morning calisthenics. Around 8,700 Columbia students, faculty, staff, and alumni ultimately served in World War I and at least 200 lost their lives in the conflict (according to contemporary university records).

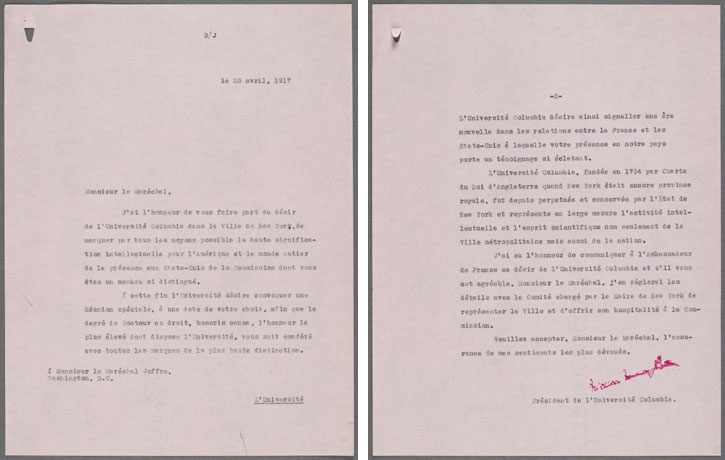

French military commanders and political leaders received a heroes’ welcome at Columbia both during and after the war. When Marshal Joffre and former French Prime Minister René Viviani toured the U.S. in April–May 1917 to drum up American support for the war, Butler invited them to Columbia, where, with reverential speeches, they were awarded honorary doctorates before a large outdoor crowd. After the war, on a chilly day in November 1921, Butler presented honorary doctorates to French Prime Minister Aristide Briand and Marshal Ferdinand Foch, Supreme Commander of the Allied Armies, at an outdoor ceremony that drew 20,000 witnesses.

In the context of World War I, Columbia committed itself fully to a liberal arts model, creating the core curriculum. “Introduction to Contemporary Civilization” got its start as a course on “War Issues” for students in army training, designed to instill awareness of the broad cultural values and moral issues at stake in the conflict. After the Armistice, the faculty redesigned the course to address “issues of peace,” including imperialism, nationalism, and industrialism, and to define the shared values of Western civilization that tied the U.S. to Europe.

French-American friendship was fortified by the wartime alliance. There were many signs of this growing amity in French university life: the enrollment of 5,800 American soldiers in French universities after demobilization; the establishment of an American University Union in Paris, with 140 member colleges and universities, created during the war to serve the needs of American college men in overseas war service and maintained after the war to help the estimated 5,000 American students living in Paris by 1930; the founding in 1920 of the American Library in Paris, stocked with books originally donated for American “doughboys” fighting in Europe; and the institution of the “Course on American Literature and Civilization” at the Sorbonne, as well as the creation of an American Library at the university (a project initiated by Butler for the Carnegie Endowment).

On the U.S. side, some 200,000 soldiers studied French during the war and an even greater number served in France. This broad exposure, coupled with pervasive pro-French and anti-German propaganda in the U.S. during the war (when the study of German was repressed and even outlawed in many states), increased American affections for France and contributed to making French the most studied foreign language following World War I, a position it would hold for decades.